AdminSDHolder Modification – How It Works and Defense Strategies

Modifying the AdminSDHolder security descriptor is a stealthy Active Directory (AD) attack technique where an adversary changes the protected ACL used by AD to protect high-privilege accounts and groups. By changing the AdminSDHolder ACL — or otherwise manipulating the adminCount/SD propagation process — an attacker can grant persistent, domain-wide rights to non-privileged accounts, create shadow admins, or bypass controls that normally prevent privilege escalation. The result can be long-lived domain compromise, data access, and near-undetectable persistence.

Attribute | Details |

|---|---|

|

Attack Type |

AdminSDHolder / SDProp manipulation (ACL abuse) |

|

Impact Level |

Very High |

|

Target |

Active Directory domains (enterprise, government, service providers) |

|

Primary Attack Vector |

Modified AdminSDHolder ACL, abused ACL write permissions, compromised privileged/delegated accounts |

|

Motivation |

Privilege escalation, persistent backdoors, domain takeover |

|

Common Prevention Methods |

Restrict write rights to AdminSDHolder, monitor AdminSDHolder/adminCount changes, tiered admin model, PAM/JIT for privileged access |

Risk Factor | Level |

|---|---|

|

Potential Damage |

Very High — domain-wide compromise possible |

|

Ease of Execution |

Medium — requires some privileges or a path to modify AD ACLs |

|

Likelihood |

Medium — many environments expose weak ACL delegation or stale permissions |

What is AdminSDHolder modification?

AdminSDHolder is a special container in AD (CN=AdminSDHolder,CN=System,DC=...) that holds a security descriptor used to protect privileged accounts and groups. The SDProp process periodically copies that descriptor to objects whose adminCount attribute equals 1, ensuring those objects retain a hardened ACL and are not weakened by normal ACL inheritance. An attacker who can modify AdminSDHolder’s ACL — or create a privileged object with manipulated ACLs or adminCount — can have that change automatically applied to many privileged accounts via SDProp.

How does AdminSDHolder modification work?

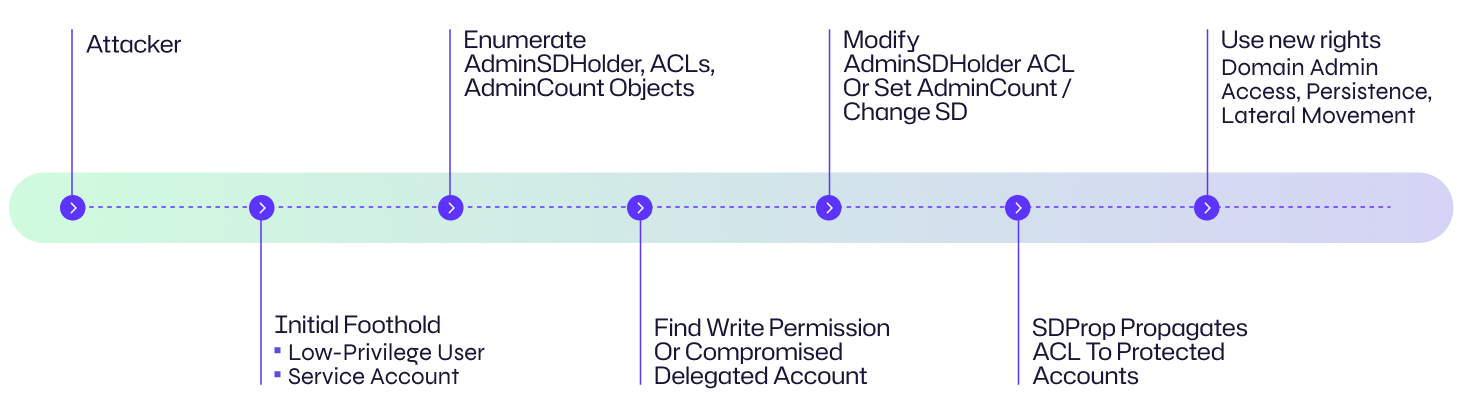

Below is a typical attack chain showing how adversaries abuse AdminSDHolder and related behaviors.

1. Get an initial foothold

The attacker gains access in the domain — for example: a low-privilege domain user, a compromised service account, delegated admin (Account Operators, Schema Admin, etc.), or a misconfigured automation credential. They may also exploit an exposed management interface or vulnerable host.

2. Reconnoitre AD protection and ACLs

From the foothold, the attacker enumerates directory objects to discover the AdminSDHolder object and its ACL, who has Write/Modify permissions on AdminSDHolder and CN=System, the set of accounts with adminCount=1, and membership of privileged groups. Tools: PowerShell Get-ACL, LDAP queries, ADSI scripts.

3. Identify a modification path

The attacker looks for a path that allows changing ACLs on AdminSDHolder (e.g., an incorrectly delegated user or an over-permissive group such as Account Operators or a service account with DS write rights). Automation/service accounts with elevated AD write rights or abandoned accounts with lingering permissions are attractive targets.

4. Modify AdminSDHolder or protected object ACL

If permitted, the attacker modifies the AdminSDHolder security descriptor to add an ACE granting a chosen principal powerful rights (WriteDacl, FullControl, WriteProperty). Alternatively, they can change ACLs on an individual protected account or set adminCount=1 on a backdoor account. Methods: Set-ACL, LDIF, ldapmodify, native Windows APIs.

5. Wait for SDProp to propagate

SDProp runs periodically on domain controllers and propagates the AdminSDHolder descriptor to all objects where adminCount=1. Once propagation occurs, the malicious ACE is applied to protected accounts — often Domain Admins — granting the attacker persistent elevated access.

6. Use elevated rights to persist and move laterally

With the new ACLs, the attacker can take control of domain admin accounts (if allowed), read/modify sensitive configuration (GPOs, trusts), create additional service principals or shadow admin accounts, and maintain persistence that survives simple remediation if ACL changes aren’t detected.

✱ Variant: Direct adminCount or single-object SD modification

An attacker with ability to modify individual objects can set adminCount=1 on a chosen account, making it a target for SDProp, or directly replace the security descriptor of a high-value account. Both variants can yield durable privileged access.

Attack Flow Diagram

Example: Organization Perspective

An attacker compromises a service account used by a legacy backup tool. That service account has delegated write permission to a subtree under CN=System. The attacker writes an ACE granting their attacker account FullControl on AdminSDHolder, waits for SDProp, and then uses the resulting elevated privileges to take control of domain admin accounts and export domain secrets.

Examples (real-world patterns)

Case | Impact |

|---|---|

|

Delegation misconfiguration |

Attackers abused delegated rights (service accounts/automation) to change AdminSDHolder, producing tenant-wide elevated rights. |

|

Shadow admin creation |

An attacker set adminCount=1 for a backdoor account and engineered SD changes so the account inherited privileged ACLs. |

Consequences of AdminSDHolder modification

Altering the AdminSDHolder descriptor or protected objects can have devastating effects:

Financial Consequences

Compromise of privileged accounts can lead to theft of IP, financial records, or customer PII, followed by regulatory fines, incident response costs, legal fees, and possible ransom demands.

Operational Disruption

A domain compromise undermines authentication and authorization across the environment. Services may be disabled, AD may need careful remediation or rebuilds, and business operations can halt during recovery.

Reputational Damage

Evidence of domain compromise signals significant security failures and can damage customer trust, partner relationships, and public reputation.

Legal and Regulatory Impact

Exposure of regulated data can trigger GDPR, HIPAA, or industry-specific compliance actions, investigations, and fines.

Impact Area | Description |

|---|---|

|

Financial |

|

|

Operational |

Auth outages, service disruptions, recovery workload |

|

Reputational |

Loss of trust, contractual penalties |

|

Legal |

Fines, lawsuits, regulatory scrutiny |

Common Targets: Who is at risk?

Accounts protected by AdminSDHolder

Domain Admins, Enterprise Admins, Schema Admins, Administrators

Service accounts and delegated non-human principals

Service accounts accidentally granted write rights to system containers

Legacy automation

Backup tools, monitoring agents, DevOps scripts with AD write capabilities

Large, poorly-audited AD estates

Many delegated permissions and stale accounts

Risk Assessment

Risk Factor | Level |

|---|---|

|

Potential Damage |

Very High — domain control and broad data access possible. |

|

Ease of Execution |

Medium — needs either a path to write AD ACLs or a compromised delegated account. |

|

Likelihood |

Medium — occurs in environments with weak delegation hygiene or unmanaged automation credentials. |

How to Prevent AdminSDHolder modification

Prevention requires reducing who can edit AdminSDHolder and improving detection & governance.

ACL & Delegation Hygiene

Restrict permissions on CN=AdminSDHolder: only a minimal set of trusted high-privilege principals should have WriteDacl, WriteOwner, or FullControl. Audit delegated permissions under CN=System and revoke excessive rights. Avoid granting AD write to non-privileged service accounts; use dedicated, controlled privileged identities for automation.

Privileged Access Management (PAM)

Use JIT/just-enough access for admin tasks rather than standing privileges. Use managed service accounts (gMSA) and short-lived certs/secrets for services where possible.

Hardening & Account Controls

Harden emergency access / break-glass accounts, disable or remove legacy/unused service accounts, and enforce lifecycle management.

Change Control & Separation of Duties

Require multi-person approval for changes to critical AD objects (AdminSDHolder, domain root ACLs). Log and review change tickets tied to ACL changes.

Baseline & Integrity Checks

Keep a baseline copy of AdminSDHolder’s security descriptor and periodically compare it to the live object; alert on drift. Regularly scan for adminCount=1 objects and unexpected accounts in privileged groups.

Detection, Mitigation and Response Strategies

Detection

- Audit and alert on writes to CN=AdminSDHolder: enable Directory Service auditing (DS Access) to capture modifications to AdminSDHolder and generate alerts for attribute nTSecurityDescriptor or DACL changes.

- Monitor for changes in adminCount: alerts when adminCount is set to 1 for unusual accounts.

- Alert on new ACEs granting non-admin principals high rights on protected objects.

- Watch for spikes in modifications to protected accounts (password resets, ACL changes).

- Monitor group membership changes for privileged groups and unexpected additions.

Response

- Immediately remove malicious ACEs and restore AdminSDHolder to the last known good security descriptor (or from a verified backup).

- Revoke the attacker’s access: disable accounts, rotate credentials, revoke service account certificates/secrets that were used.

- Invalidate authentication sessions where possible (force Kerberos ticket purge, enforce reauthentication).

- Perform a domain integrity and impact assessment: enumerate where the malicious ACE was propagated, identify compromised privileged accounts, and search for lateral artifacts.

- Perform credential resets for affected privileged accounts and rotate service secrets.

- Hunt for persistence: check for created service principals, scheduled tasks, GPOs with malicious scripts, or modified delegation entries.

Mitigation

- Limit future exposure by removing unnecessary write delegations, tightening controls, and implementing PAM/JIT for admin activities.

- Improve auditing and integrate alerts into IR playbooks to accelerate detection and containment.

How Netwrix Can Help

Netwrix Threat Prevention helps you stop AdminSDHolder abuse by detecting and blocking unauthorized changes to critical AD objects in real time. It creates a complete, tamper-resistant audit trail for object and attribute changes, and can automatically alert on or prevent risky actions like DACL edits and privileged group or GPO modifications, reducing the window for persistence and domain takeover. Teams can tailor policies to lock down sensitive containers and enforce immediate response when AdminSDHolder or protected accounts are touched, strengthening data security that starts with identity.

Industry-Specific Impact

Industry | Impact |

|---|---|

|

Healthcare |

Loss of domain control could expose EHR systems and patient data, risking HIPAA violations and operational disruption. |

|

Finance |

Domain compromise enables access to financial systems, transaction logs, and customer PII — high regulatory & fraud risk. |

|

Government |

High risk of espionage and national security impact if privileged domains are abused. |

Attack Evolution & Future Trends

- Automation of ACL reconnaissance — attackers are automating searches for writeable system containers and delegated permissions in large AD estates.

- Combination with other AD attacks — AdminSDHolder abuse is combined with Golden Ticket / DCSync / ACL abuse chains for robust persistence.

- Supply-chain and DevOps exposure — leaked automation credentials in pipelines continue to surface as vectors for delegated ACL modifications.

- Fewer noisy actions, more stealth — attackers prefer ACL/DACL manipulations because they blend in with legitimate admin activity.

Key Statistics & Telemetry (suggested checks)

• Percentage of domains with non-standard write permissions to CN=System or AdminSDHolder (measuring hygiene).

• Count of accounts with adminCount=1 and no recent legitimate admin activity.

• Number of service accounts with AD write privileges in the environment.

Final Thoughts

AdminSDHolder modification is a high-impact, stealthy technique: by attacking the mechanism AD uses to protect privileged accounts, attackers can achieve durable, domain-wide privilege escalation that survives many simple remediation steps. Defending against it requires strict ACL governance, least-privilege delegation, strong privileged access controls (PAM/JIT), continuous auditing of AdminSDHolder and adminCount objects, and rehearsed response playbooks to quickly remove malicious ACEs and rotate impacted credentials.

FAQs

Share on

View related cybersecurity attacks

Kerberoasting Attack – How It Works and Defense Strategies

Abusing Entra ID Application Permissions – How It Works and Defense Strategies

AS-REP Roasting Attack - How It Works and Defense Strategies

Hafnium Attack - How It Works and Defense Strategies

DCSync Attacks Explained: Threat to Active Directory Security

Golden SAML Attack

Understanding Golden Ticket Attacks

Group Managed Service Accounts Attack

DCShadow Attack – How It Works, Real-World Examples & Defense Strategies

ChatGPT Prompt Injection: Understanding Risks, Examples & Prevention

NTDS.dit Password Extraction Attack

Pass the Hash Attack

Pass-the-Ticket Attack Explained: Risks, Examples & Defense Strategies

Password Spraying Attack

Plaintext Password Extraction Attack

Zerologon Vulnerability Explained: Risks, Exploits and Mitigation

Active Directory Ransomware Attacks

Unlocking Active Directory with the Skeleton Key Attack

4 Service Account Attacks and How to Protect Against Them

How to Prevent Malware Attacks from Impacting Your Business

What is Credential Stuffing?

Compromising SQL Server with PowerUpSQL

What Are Mousejacking Attacks, and How to Defend Against Them

Stealing Credentials with a Security Support Provider (SSP)

Rainbow Table Attacks: How They Work and How to Defend Against Them

A Comprehensive Look into Password Attacks and How to Stop Them

LDAP Reconnaissance

Bypassing MFA with the Pass-the-Cookie Attack

Silver Ticket Attack